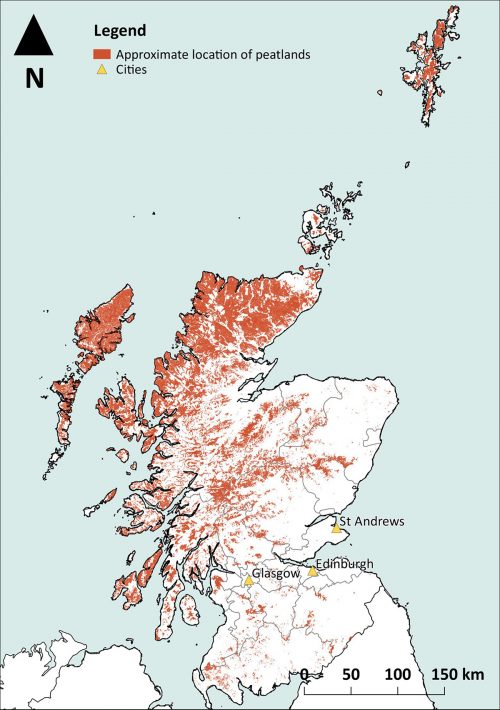

Peatlands make up over 20% of the land area in Scotland. Spread over 17,000 km2, these vital ecosystems store an estimated 1,620,000,000 tonnes of carbon. That’s about half of the area and quantity of carbon compared to the Pastaza-Marañón Basin in Peru. In contrast to the mostly intact Amazon peatlands, however, over 80% of Scotland’s peatlands are thought to be degraded.

Peatlands form in Scotland for the same reasons they form in Peru: waterlogged soil conditions slow the rate of decay of plant litter and allow semi-decomposed organic matter to build up over time. As in Peru, there are several different types of peatland in Scotland, including fens and raised bogs.

Blanket bog, the most common type of peatland in Scotland, stretches as far as the eye can see here in Glen Clova in the Angus Glens. A layer of peat blankets the landscape where conditions are right and can reach up to eight metres thick in places. Peatlands here tend to be open, rather than forested as in Peru, and are dominated by mosses and sedges, heather and bilberries. Where trees do grow it can be a sign that a bog is drying out, and/or that they were planted.

Bog cotton, Eriophorum angustifolium, is a sedge. In summer its tufted flowers signal the presence of peat. Below it, the bog surface is often a wet spongy carpet of ruby red and bright green Sphagnum moss.

Sphagnum moss is the key ’bog builder’ of Scotland’s peatlands. It plays a similar role to the Mauritia palms pictured in the Peruvian swamps, often contributing the majority of organic material in the peat. Sphagnum has no roots but its leaf cells can hold over 20% of its dry weight in water. This has made it useful historically for dressing wounds and today as an ingredient in garden compost.

The peat sample pictured left was taken from the top 30 cm of one of the few raised bogs in lowland eastern Scotland, Portmoak Moss. Below the present day mix of moss and shrubs at the top of the core are the remains of plants that grew at this spot over the last 300 years, dominated by Sphagnum moss.

Similar to peat cores from Peru, the pollen and chemical signals preserved in the peat will be analysed in the lab to understand how the peatland has changed over time to inform present conservation activities.

Like many Scottish peatlands, Portmoak Moss has been drained and planted for timber in the past, but it is currently being restored. Trees have been removed and drainage channels blocked in an effort to return the bog to a wetter, more natural state.